Gail Tverberg has many ideas that we will encounter again throughout this blog series. Besides the connection between economic growth and energy, her ideas are primarily based on the realization that capitalism relies on the pre-financing of production. This pre-financing can only be funded with future growth. As a result, a capitalist system is doomed to grow. This will cause problems in the long run.

The word capitalism is not used pejoratively here, but it is something different from a market economy. Such thoughts were completely foreign to Ludwig von Mises, who never worked a day in the private sector in his life. Companies need to “save” to “make investments,” as one might think at a desk. In reality, almost all major companies are heavily indebted, and these debts can only be repaid with future economic growth.

Mises’ ideas, on the other hand, describe, albeit perfectly, essentially only medieval barter economies. These are indeed stable, but have nothing to do with modern, debt-financed capitalism. See also Gail’s post “There is No Steady State Economy (except at a very basic level).” Societies like the Amish are indeed much more stable than ours.

But now to “How Does the Economy Really Work?” From Gail Tverberg. Repost kindly granted via Creative Commons License.

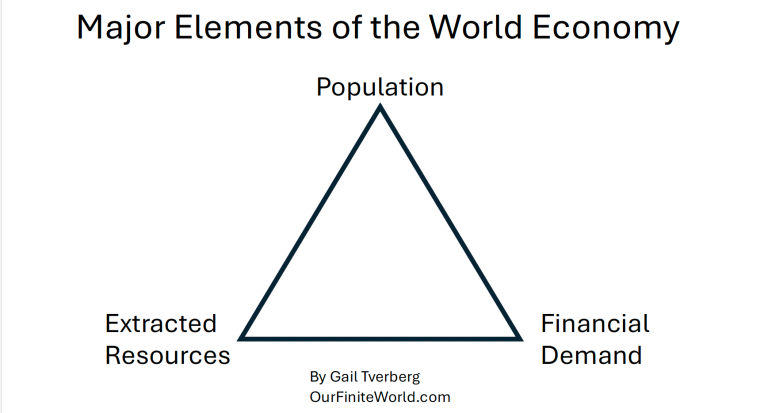

The world economy is an amazingly complex, physics-based, self-organizing system. The three major elements are extracted resources including energy resources, human population, and demand coming through the financial system.

Figure 1. Major elements of the world economy according to Gail Tverberg. These are human population, extracted resources including energy resources, and financial demand.

All three of these elements tend to increase over time, but both population and extracted resources tend to hit limits because the world is finite. Financial demand is emphasized by politicians because it seems to increase without limit. The extraction limit is not obvious: It is the amount that consumers can afford to pay for resources and the products they create. This limit cuts off resource extraction at amounts that are far below the amounts that geologists calculate are available for extraction.

In this post, I will offer some insights into how the world economy actually operates.

The fitted years are 1965 to 2023. The R2 =.98 tells us that there is a close relationship between energy consumption and GDP.

Physics tells us that every action, even the movement of molecules, requires energy dissipation. Within the economy, this energy can be human energy, energy from the sun, or energy from sources such as burned biomass or fossil fuels.

In physics terms, the world economy and many structures within the world economy are dissipative structures. These structures are self-organizing, and they often grow over time. Examples are plants and animals, hurricanes, and businesses.

Dissipative structures require energy of the right kinds for their continued “life” and for growth. Animals require food for their continued life and growth. Hurricanes get their energy from warm sea water. The fact that the economy is a dissipative structure has been known since 1996 and is written about today.

According to Discover Magazine, pre-humans first began to build fires to cook food at least 800,000 years ago. The consumption of cooked food allowed early humans to have bigger brains, smaller teeth and jaws, and more time for activities other than chewing, such as making crafts.

Humans are now adapted to having some cooked food in their diets to get adequate nutrition. (A few people today try to consume a raw food diet, but they often use a food processor or juicer to break down cell walls.) As a result of the adaptation to eating some cooked food, two major changes took place:

(a) Humans were able to achieve dominance over other plants and animals. They could use fire directly to scare away other animals, and they could use fire to help make better tools for hunting and agriculture.

(b) Because of this dominance, the population of humans has tended to grow until some kind of limiting condition is hit. The resulting pattern is often called overshoot and collapse.

History shows a repeated pattern of overshoot and collapse. A population would grow until the carrying capacity of the local area was reached. Food surpluses would become lower and lower, so less food could be saved up for fluctuations in rainfall and temperature. Eventually, civilizations would succumb to one or another problem: disease, attack by a neighboring group, climate fluctuations, or governments overthrown by unhappy citizens.

We tell ourselves that overshoot and collapse cannot happen now, but human population is high relative to fossil fuel resources, and intermittent wind and solar are not working out well as substitutes.

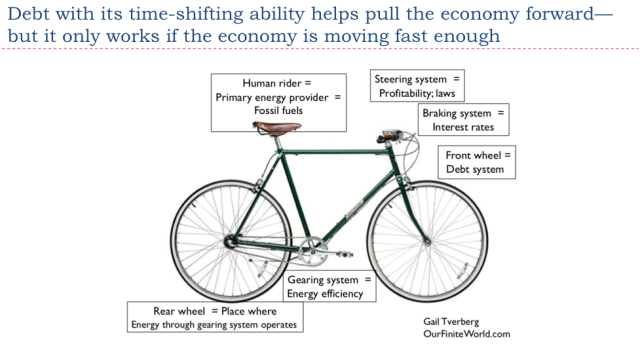

Figure 3 shows my view of how the economy works. Debt is indeed important because it helps pull the economy forward. For example, it helps an entrepreneur afford to build a factory and hire workers. As long as the investment pays back well enough to repay the debt with interest, the system seems to work. GDP tends to grow. (Figure 3 also shows five other parts of the system, but I am leaving these to the reader to review.)

Debt is not unique in pulling the economy forward. Shares of stock issued with the promise of dividends act similarly to debt because they allow investment before a new product is made. Pension plans, even if not funded, stimulate the economy because citizens decide that they don’t need to save for the future (or have children), if they can depend on the government pension plan to take care of them. Even inflation in the price of a home or shares of stock can have the effect of adding to demand. For example, a person owning shares of stock can sell some appreciated shares of stock and use the proceeds to build a new factory.

It is the time-shifting aspect of debt and related promises that is important. With the help of debt and its equivalents, people can spend today to build a road or factory that will provide a long-lasting benefit. The hope is that the total return will be high enough that the debt can be repaid with interest, or that dividends can be paid on the shares of stock.

If the economy is growing quickly, interest rates can be quite high without slowing the economy. If energy costs are very high, or if all industries are stagnant, it may be difficult to get any payback at all from a debt-related investment. Instead, interest rates may need to be very low, or debt defaults become likely. Economic growth is likely to be low, or even negative.

In one their analyses of borrowing by governments over eight centuries, Reinhart and Rogoff unexpectedly discovered the phenomenon of low defaults among rapidly growing countries. They reported, “It is notable that the non-defaulters, by and large, are all hugely successful growth stories.”

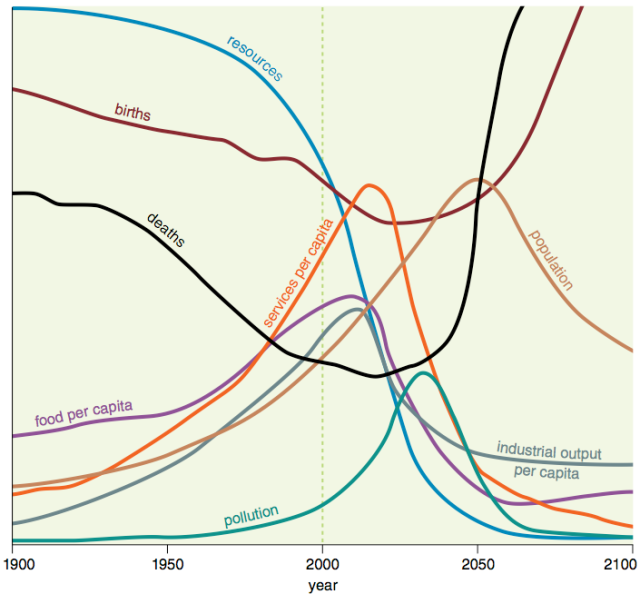

The easiest models to build are ones that assume the future will be very similar to the past, or that the trend from the past will continue. These models tend to be popular with citizens because they suggest that good times will continue indefinitely. Such outcomes are what everyone would like to see, so these models tend to be accepted as “scientifically valid.”

In a finite world, many kinds of patterns are constantly changing. Depletion of resources and rising population are particular stressors. Figure 4 shows the base scenario of a 1972 computer model of resource depletion, population growth, and pollution growth.

The model used was an engineering-type analysis of the physical quantities involved. This approach did not show growth continuing indefinitely. Instead, it showed a major downturn about now.

I have looked at the model myself, and I have talked with Dennis Meadows, who oversaw the analysis. The model looks at resources used in each six-month calendar period. The share of these resources needed for getting these resources out and transformed into usable work cannot be too high, or the economy tends to collapse. (Nature doesn’t use accrual accounting!)

In such a calculation, quick payback of an energy investment becomes very important. Also, the amount of supplementary equipment, such as electricity transmission lines and batteries required, becomes important. I would expect that wind, solar, nuclear, and liquefied natural gas (LNG) would do relatively poorly in such a calculation. Oil, coal, and burned biomass would do much better because their energy payback is immediate–when they are burned. Furthermore, oil, coal and biomass require relatively little specialized equipment for transportation and storage.

One popular narrative is that Financial Demand is all that really matters. Politicians have significant control over the Financial Demand shown in Figure 1. They can see that if they can create more debt, they can perhaps get some of the money that the debt makes available down to ordinary citizens. With more money, citizens can perhaps buy more goods and services from the world economy.

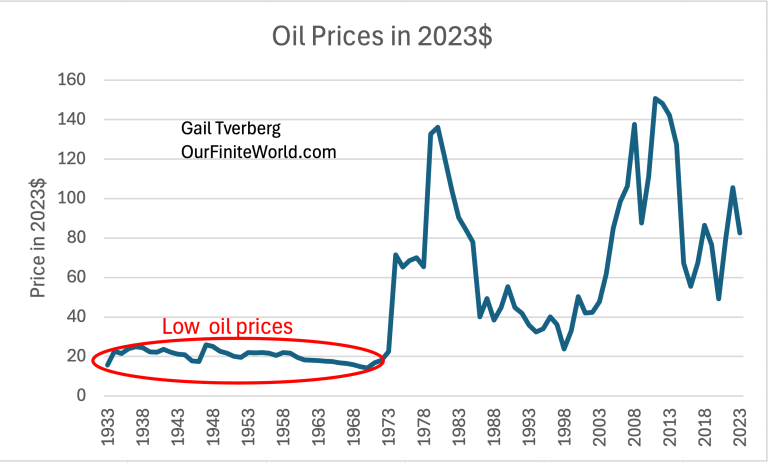

Historically, raising financial demand has worked well because the extraction of fossil fuels and many other resources were well within physical extraction limits. Higher demand would lead to higher prices, which in turn would lead to more extraction. But as we get closer to the physical extraction limits, this approach works less well. The problem is that at some point, finished goods (such as automobiles and groceries) become too expensive for consumers if prices rise high enough to satisfy producers.

Because we are now reaching extraction limits, the added debt approach works much less well, as the short tenure of Liz Truss as Prime Minister of the UK in 2022 shows. The problem for countries other than the US is that with added debt, their currencies tend to drop relative to the US dollar. Thus, while perhaps their citizens can individually buy more, the cost of imported goods and services, especially energy, tends to rise. Overall inflation tends to be higher. This causes citizens to become very unhappy.

The US is in a unique position because it is currently the holder of the “reserve currency.” Its currency can’t drop relative to the US dollar. However, since 2020, the US has added huge amounts of debt, as have other countries around the world. Asset prices have also risen because of temporarily low interest rates. Newly made goods and services don’t increase in proportion to the rapidly growing debt and other financial stimulus. What tends to happen instead is inflation, as we have recently witnessed.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t work. Affordability is important to the consumer, so oil prices can’t rise too high. At the same time, prices cannot fall too low, for too long, or producers will stop extracting oil. Instead, oil prices tend to spike and then fall back. They are to some extent not very acceptable to either buyer or seller. Whether the buyers or sellers are more disadvantaged varies over time. A similar pattern holds for other resources, as well.

Unfortunately, the world economy can no more move away from fossil fuels than humans can move away from eating food. In fact, moving away from fossil fuels would likely lead to starvation for a large share of the world’s population. In 1798, Thomas Malthus wrote about his concern that population was growing too fast relative to food supply. The timing was shortly before fossil fuels began being used very widely. World population at that time as only about 1 billion. World population today is over 8 billion.

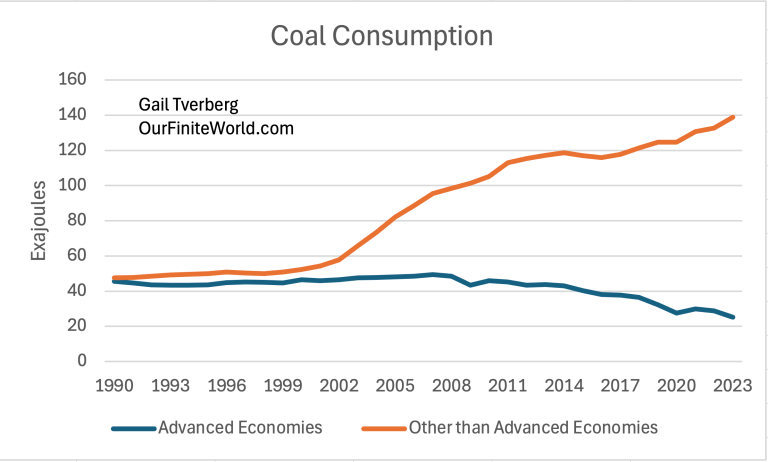

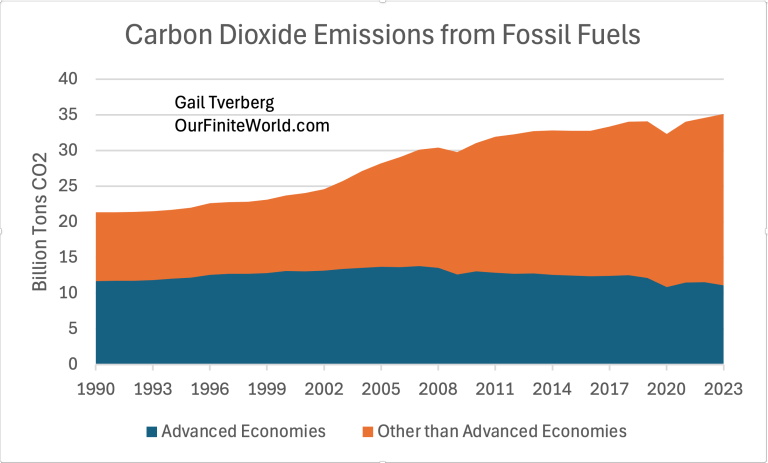

In part, the climate change narrative seems to be an excuse to move manufacturing from Advanced Economies to economies that make extensive use of coal, as it tends to be a cheap fuel. The latter economies also tend to have lower wage and benefit levels, so there is a definite cost advantage. China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. The result is easy to see in Figure 8 below. The US now exports coal to India and China, among other countries.

As a person might expect, world CO2 emissions from fossil fuel use have soared.

While the narrative we hear endlessly is “We are moving away from fossil fuels to prevent climate change,” I believe the real issue is that fossil fuels are leaving the world because we are hitting extraction limits. No one wants to hear such an awful story, however. The climate change narrative is a “sour grapes” version of the story that is more palatable to listeners.

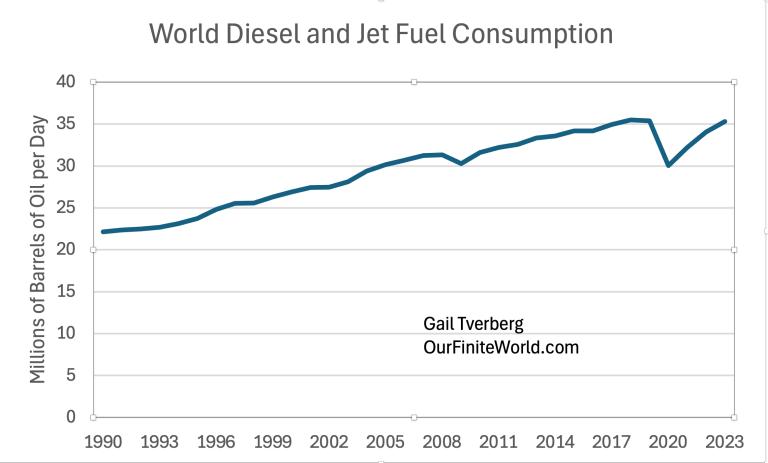

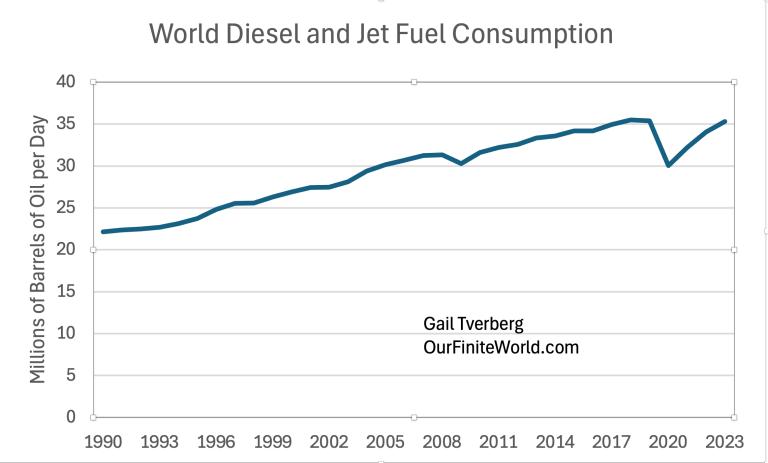

Figure 8 below shows that the year 2020 should have been a wake-up call that the world needs to cut back on diesel and jet fuels. Diesel fuel is heavily used by agricultural machinery, large trucks, trains and boats. Of course, jet fuel powers jets. With rising world population and a growing economy, it would be expected that the consumption of these heavy oils would continue to grow.

Between 1990 and 2018, consumption of diesel and jet fuels increased by an average of 1.7% per year. Between 2018 and 2023, there has been no increase at all–in fact, world consumption for 2023 is slightly lower than in 2018. If the 1.7% per year growth pattern had continued, consumption of this combination of fuels would have grown by 8.8% during the five-year period from 2018 and 2023.

In a sense, there is a shortfall of approximately 8.8% of the diesel and jet fuel combination. Some airline schedules (especially in Asia) have been cut back. Farmers in Europe are protesting because the selling prices for the crops they grow are not high enough to cover today’s diesel and fertilizer costs plus other costs of production. Diesel is a problem fuel and fertilizer is very energy dependent. If the price of groceries rises high enough to cover the costs of diesel and fertilizer for farmers, grocery costs become unaffordable to many citizens.

Complexity can take many forms, including greater specialization; more education for some of the workers; larger, more hierarchical businesses; greater globalization; and ever more complex devices. Such devices can often use energy products more sparingly. Because of these potential energy savings, many people assume that such devices can allow the energy supply that is available to be stretched to cover all the economy’s needs.

In practice, it doesn’t work this way. Instead, added complexity often adds to energy demand instead of reducing it. For example, moving significant manufacturing to China starting in late 2001 was a type of added complexity. This change added to world coal demand and increased CO2 emission because the goods produced in China and shipped elsewhere were cheaper and therefore more affordable than goods made in the US or Europe.

Another issue with complexity is the susceptibility to breakdowns it produces. Just this past week, there was an example of this with the update of CrowdStrike computer software that took down computer networks around the world. Another example is the problem Kia is having with engines shutting down unexpectedly. Nature uses complexity, but it also incorporates redundancy so that unexpected breakdowns are not a frequent result.

A third problem with complexity is that it leads to supply chains for practically everything manufactured in the US or Europe needing to go through China. This makes the US and Europe dependent upon suppliers in China. Even military goods have supply chains running through countries that we are at odds with, including China. This means that China can, in many ways, “hold the US hostage,” by refusing to sell the US rare earth minerals, or by refusing to provide parts of supply chains needed for military armaments.

Perhaps the most important problem of all with added complexity is the wage and wealth disparities that it leads to. With added complexity, there is more specialization. A few workers with considerable training and advanced degrees get high paying jobs. The wages for these workers, plus the wages for managers, leave little funding left over for less trained workers. Also, competition with workers in low wage countries tends to hold down wages for less-skilled workers.

Besides the wage disparities, some people, mostly those who are already high-wage earners, become owners of these companies. If stock prices rise, this increases the wealth disparities between the rank-and-file workers and those at the top of the hierarchy. The higher-wage people also tend to purchase homes, and the price-appreciation on their homes adds to their wealth.

Physicist Francois Roddier, in his book The Thermodynamics of Evolution, explains that this growing wage and wealth disparities are to be expected when energy supplies are short, and added complexity is attempted as a substitute. Already wealthy people tend to get a disproportionate share of the goods and services produced by the economy, while poor people increasingly get squeezed out because of the physics of the situation.

I believe this issue is behind the conflict we are experiencing today. I will leave this issue for another post.

This is another issue that I will leave for another post.

I hope these thoughts are somewhat helpful. I have only touched on a few aspects of how the economy really works. Perhaps I can offer more ideas on this subject in the future.

Capitalism requires future growth to pay off huge investments. This is the essence of modern capitalism that uses, besides technology and energy, debt for pre-financing the production of goods. Most public companies drown in debt. This debt can only be repaid with future growth. This is something that is unique to capitalism as seen in the last, give or take 150 years. In contrast, a market economy in the Middle Ages, or one like the Amish, can function without this. A system on such a low level could be stable forever.

What is your backup plan? Talk to us.